Kochia: Fight smarter, not harder

April 30, 2025

Kochia continues to expand its footprint north and east across the Prairies and producing herbicide resistant populations at an alarming rate. It’s a particularly troublesome weed but take heart — there are a raft of options to manage kochia without breaking the bank

By Trevor Bacque

Kochia is definitely an A-list weed. Its methodical march across the Prairies appears to be extraordinarily suited to this landscape, says Charles Geddes a research scientist specializing in weed ecology with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge, AB. He should know — he’s been watching that march for the last 15 years.

What makes kochia so successful? First, it’s a prolific seed producer and spreader. In competitive environments, a single plant produces up to 20,000 seeds. If left unchecked, 100,000-plus seeds per plant is not unusual. Then, as a tumbleweed, it spreads those tens of thousands of seeds far and wide. It has more tricks up its stem, too.

Kochia differs from other summer annuals in that it doesn’t produce the bulk of its seed until mid-August or later, whereas most other weeds are mature by late July to early August. Post-harvest management is vital, says Geddes, since kochia can be cut down at harvest, grow back, set seed and spread — all before killing frost sets in.

Then there is kochia’s remarkable ability to develop herbicide resistance. “The populations are highly genetically diverse,” explains Geddes. “That means there is greater frequency of mutations that may allow it to become resistant. It has a unique type of flowering that makes it an efficient out-crossing plant. It can transfer resistance traits through pollen and seed contamination. Combine that with how it thrives under abiotic stress, it makes for a weed that is able to overcome a lot that we throw at it.”

In Canada, kochia populations resistant to groups 2, 4, 9 and 14 have been documented. In the U.S., it’s that same list, plus Group 5.

AAFC’s most recent post-harvest weed survey showed there is near-universal resistance to Group 2, so if you see kochia, assume it’s Group 2 resistant. As well, glyphosate resistance, which first appeared in 2011, now sits at 74 per cent Prairie-wide. “It does surprise me,” says Geddes. “This is one of the fastest spreads of resistance I have observed.”

Pre-emptive control is key

While post-harvest kochia control is key to minimizing seed return to the weed seed bank, when it comes to protecting yield potential, the best time to grapple with kochia is during pre-seed burndown. Since it’s one of the earliest plants to emerge, Geddes says the best window for attack is before kochia hits 10 cm in height. After that, farmers are on borrowed time.

“Once it gets up to 10 cm or more, lots of the products registered for control are no longer effective,” he says. “Managing it at that time is really important.”

Geddes says most farmers practice minimum- or zero-tillage and have largely opted for glyphosate burndown over the last 15 to 20 years. “In part, that is why we have seen such a rapid spread of glyphosate resistance,” he says. “Based on its biology, soil disturbance or tillage is effective against kochia, yet those have a negative impact on soil health. There is a balance farmers have to consider.”

So, if the tried-and-true glyphosate pre-seed burn carries inherent resistance risk, and you don’t want to churn up your soil, what are the options?

Cultural choices: fight the fight without breaking the bank

There are several cultural controls at farmers’ disposal to effectively knock back kochia. The first is a strong crop rotation, which should include winter annuals. Barley is the No. 1 crop to outcompete kochia, while pulses like lentils are usually the least competitive. Silage is also effective, if it fits into a farmer’s plans.

How you plant can have an impact, too. A 2018-2021 research project done by AAFC found narrower row spacing (9” vs. 18”) and increased seeding rates (400 seeds/m2 for wheat, 200 seeds/m2 for canola and 260 seeds/m2 for lentils) reduced kochia presence by 80 per cent, which is the threshold efficacy labelled control for a new herbicide. In other words, kochia control similar to that of herbicide.

“If you’re dealing with resistance, there will have to be additional non-chemical management to stay ahead of the weed,” explains Geddes. Mowing and rogueing, for example.

Herbicide choices: Mix and match

Despite the various herbicides to which kochia has developed resistance, there are effective spraying choices, says Rory Cranston, Bayer’s North American technical strategy lead. The key is to always apply multiple modes of action.

“The good news is that groups 6 and 27 haven’t broken to kochia yet,” he says. In fact, they’re a top option for control.

“Group 6 and 27 work really well together and they are protecting each other,” says Cranston. “I would cringe to do a solo Group 27 for control. If you can get a really good kochia kill with your groups 6 and 27 in a pre-burn and then good crop establishment, it makes life all that much easier for your in-crop application.”

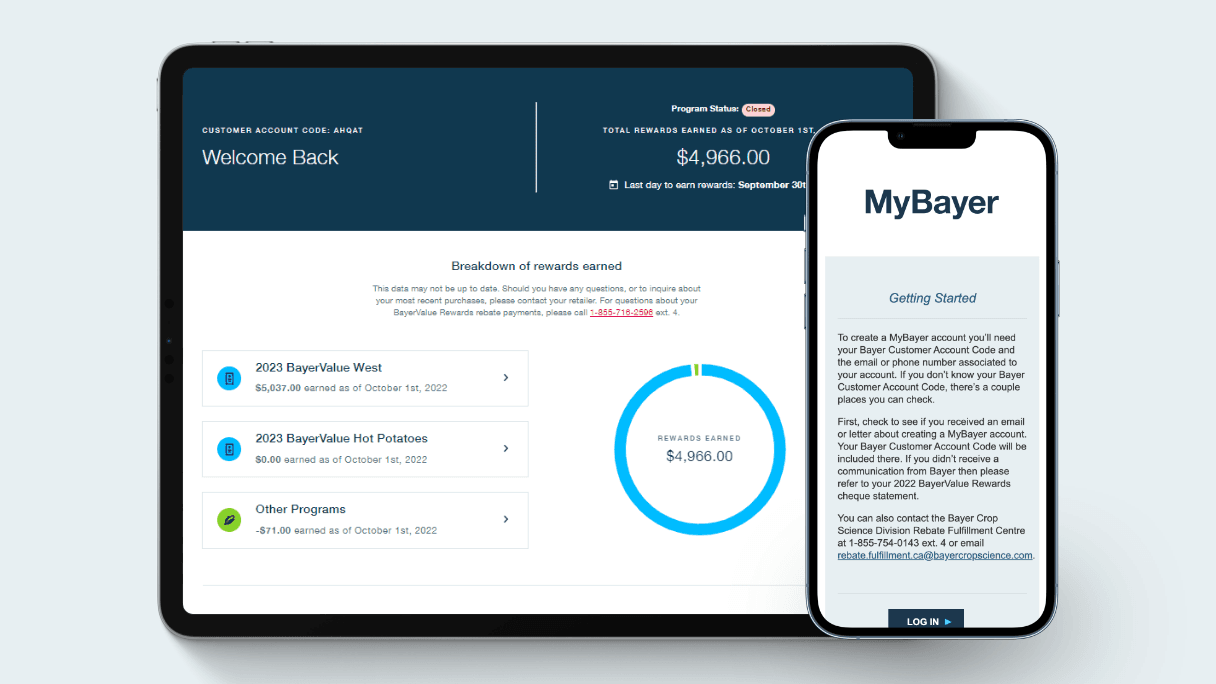

Recently introduced Bayer products Huskie PRE (groups 6 and 27) for broad leaf control prior to cereals, and Varro FX (groups 4 and 2) for wild oats and tough grasses are legitimate options.

As the name suggests, Huskie PRE is designed for application pre-seed/pre-emergence. “It has a really aggressive adjuvant package built into it and when mixed with glyphosate, it provides a lot of strong activity on kochia,” explains Cranston. “That is a great option to get your crops started and established with a clean seedbed.”

With its high dose of fluroxypyr (Group 4), Cranston sees a role for Varro FX, too. True, some kochia populations are resistant to fluroxypyr, but he says tank mixing with a Group 6 and a different Group 4, like MCPA, can help tackle kochia in specific situations.

Above all, Cranston encourages farmers to have a full-throated response to kochia. “This is a weed we don’t want to cut corners on, cut rates on or use cut products on,” he says. “If you start that, it’s going to find a way to take advantage of any gaps or holes.”

Geddes is equally serious, yet optimistic, about keeping kochia in check. “We have shown with our field experiments, the issue is manageable, even with just row spacing and seeding rates,” he says. “It’s the combination of getting a competitive crop and understanding that post-harvest management and staying on top of the patches where it’s growing well are important.”