The ins and outs of using cereal fungicides in dry conditions

June 10, 2025

Disease generally does better in warm, moist conditions. But, just because it’s hot and dry, doesn’t mean there is no disease. Here’s what the experts say about how to look for and manage cereal diseases in dry conditions.

By Trevor Bacque

The Prairies continue to be dogged by a prolonged period of dry, warm temperatures. But even in dry conditions, farmers will have to use all available tools at their disposal to look for and manage diseases, which can pop up seemingly overnight.

Kelly Turkington is a research scientist who specializes in cereal diseases on the Prairies. Over his 30-plus years in the field, he’s seen just about everything, and the one place he always encourages farmers to look is where they can’t see, namely under the canopy.

“Take note of what’s there, but don’t assume that because you’re not seeing a lot of symptoms that you don’t have a problem,” he says.

Turkington advises farmers to check the crop as it comes into stem elongation and flag leaf emergence, inspecting the third leaf from the head. If there’s no sign of disease there or lower down, you have minimal risk. However, if one to two per cent of the area of those third leaves have symptoms, along with higher disease levels in the lower canopy, you are at risk for leaf disease.

This scenario likely warrants a pre-head emergence fungicide, says Turkington, and adds that because most fungicides only provide protection for two to three weeks, farmers must ensure to prolong that protection period as far into grain fill as possible.

On the other hand, if the crop is green throughout as you check it during that stem elongation, flag leaf period, you’re probably safe. But be aware that the situation can change. Even though conditions may be dry in May and most of June, rainfall towards the end of June and into early July could lead to leaf pathogen development that threatens the crop during grain filling. So, check a final time at heading and meticulously inspect the lower part of the canopy. If the coast is clear, keep the fungicide on the shelf.

Seeing no signs of leaf disease throughout the canopy likely means that a fungicide won’t provide a solid return on investment (ROI), especially if conditions are dry. “Fungicides are not cheap,” says Turkington. “You want to make sure that you need them, use appropriate timings and that you’re going to have a response from the crop that at least covers the cost of chemicals and application.”

Diseases to watch

Persistent dryness can render cereal diseases semi-dormant and eventually limit development. Still, pay attention to daytime highs between 20 and 30 C. Above 30 C, the situation favours farmers with respect to disease, but crop productivity can dip. Turkington recommends having tissue samples sent in at tillering to determine if you’re looking at a disease pathogen or simply an abiotic stress response since the two are often confused. Here are a few things to keep an eye on this season.

Rusts. This year farmers should take special note of rusts, which affect crops during grain fill and yield. Rusts can appear suddenly and be catastrophic if established between stem elongation and flag. If risk stays moderate to high, additional fungicide applications are warranted from flag leaf to post-head emergence.

The Prairie Crop Disease Monitoring Network issues weekly rust risk forecasts from mid-May to early July, giving farmers a heads up on potential emerging rust issues based on rust development in the U.S. as well as wind trajectories that bring rust spores from there into the Prairie region.

Leaf spots. Tan spot, the septoria complex, net blotch, scald and spot blotch survive on old crop residues, providing a continuous source of inoculum during the growing season. Leaf spot fungicides work best when applied directly to upper canopy tissues prior to serious disease development.

Powdery mildew. Farmers don’t need necessarily much rainfall for powdery mildew to become an issue. “If you have high relative humidity levels in the crop canopy, that tends to be more favourable for it,” Turkington says. With significant levels found in recent years, it’s one to watch.

FHB. Similarly, managing fusarium head blight in cereals is challenging because the spray decision must be made before it appears. Check Prairie FHB risk maps and don’t rely on fungicide alone but integrate it with crop rotation and less susceptible varieties. FHB doesn’t overly affect yield, but fusarium damaged kernels and mycotoxins may cause significant downgrading.

Consult the experts

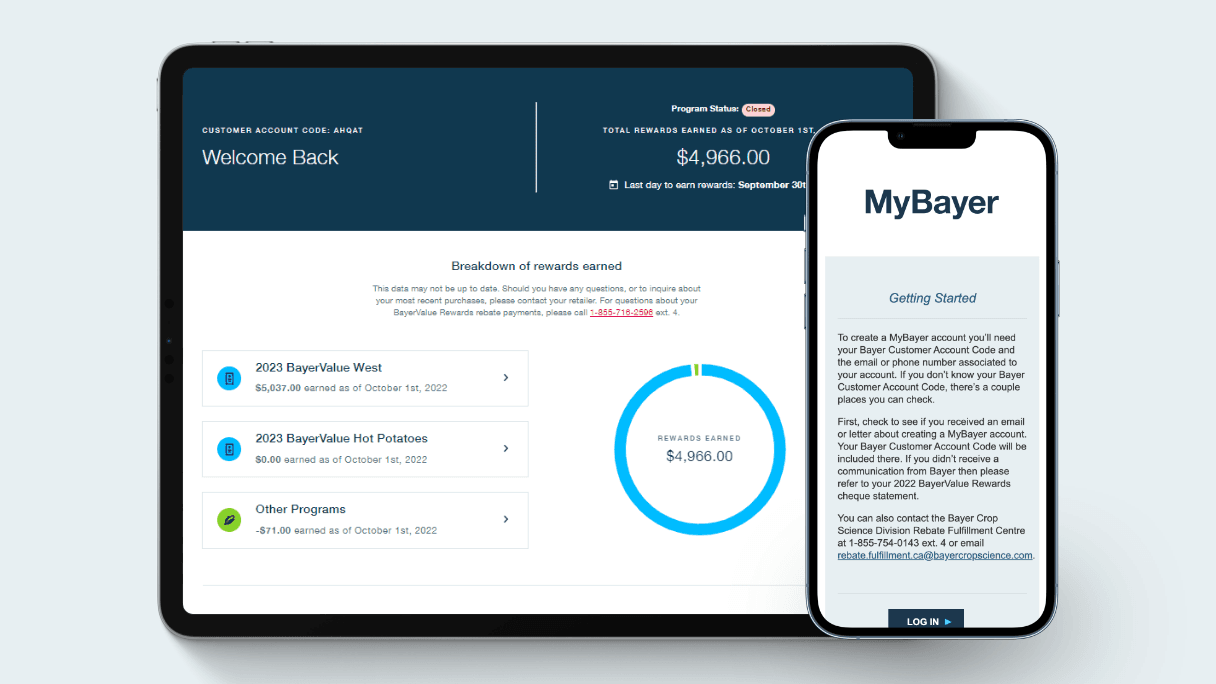

For 17 years, Bayer has run fungicide market development trials across Western Canada. The company compares its own fungicides versus competitor products in field-scale, farmer run trials to give all farmers the best picture of conditions in their area. With hundreds of site years available, farmers can use Bayer’s digital trial map (ItPaysToSpray.ca) to comb through data and understand what their best fungicide option might be.

“The whole purpose of what we’re doing is to give farmers local information that they can refer to that is relevant to their specific growing conditions and practices,” says Kate Hadley, customer solutions agronomist with Bayer in Saskatchewan. “We post our trial results, whether we win, lose or tie. We’re trying to share as much as we can about our products and what’s working in growers’ local areas.”

Hadley has run these cereal fungicide trials in Saskatchewan for the last six years and what she has noticed is that there is often an advantage to spraying a fungicide, even in dry conditions.

“Even in the really dry years, like ’22 and ’23, we were seeing about five bushels or so yield increase over the untreated check,” she explains. “That bump definitely covers the cost of the product, your equipment and time going across that field. You’re definitely making a few dollars at a five bushel increase over untreated.”

She reminds farmers to pay attention to the environment portion of the disease triangle. “Even if you have great rotations in Western Canada, you’re probably going to have some inoculum whether it’s sclerotinia or fusarium,” says Hadley. “It really comes down to what the environment is doing, not just during fungicide timing, but leading up to it as well.”

ROI aside, Hadley is also a booster of spraying as it increases a crop’s photosynthetic activity, which carries multiple benefits, including greater yield.

“Fungicides can actually help plants kind of perk up a little bit, it can help them use water more efficiently and help them stay a little bit greener,” she says, adding that there aren’t any drawbacks in terms of crop safety or plant response, and farmers will usually see a positive response from a slightly greener crop that stays alive longer during grain fill.

Hadley encourages malt barley farmers to always spray a fungicide, given the high bar set to meet malt standards and the investment to produce such a crop.

Above all, Hadley stresses, fungicides are a tool to make the first strike, not the last. “Remember that fungicides are preventative, they're not curative,” she says. “It’s always a good practice to plan for a fungicide application.”